|

|

|

an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins

photo by Alice M. Guldbrandsen

photo by Alice M. Guldbrandsen |

Roaming Literary London –

Bloomsbury and Environs

Essay and Photos by Walter Cummins

|

You could devote a lifetime – and some actually have – to roaming London as a literary explorer. Stroll down street after street to discover blue plaques on buildings that proclaim some writer you read in a survey of Brit Lit course lived there for a few years. Or follow the fictional footsteps of Clarissa Dalloway through Westminster on her morning |

quest for flowers. Or tour the locales of Eliot's Wasteland: “'This music crept by me upon the waters' / And along the Strand, up Queen Victoria Street / O City city, I can sometimes hear / Beside a public bar in Lower Thames Street . . .” And that's not to mention Dickens and Thackeray and Ben Jonson and Samuel Johnson and Evelyn Waugh and Anthony Powell. Is there a London street or park or landmark that hasn't appeared in some novel or poem or play or story over the centuries?

So what is a traveler to do to avoid being overwhelmed? My most recent strategy – other than a tube trip to Southwark to see the recon-

struction of Shakespeare's Globe Theatre – was to stay within walking distance of the flat we had rented in a narrow alley behind the Russell Square tube station. Even with that limitation, I barely touched all the possibilities.

|

|

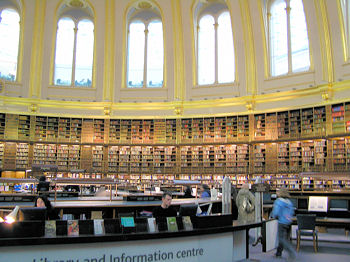

The British Library

The new – opened in 1998 – British Library at St. Pancras was just ten minutes away up Woburn Place, with a left turn on Euston Road. The young man in the nearby pub claimed the library was shaped like a ship, the design visible if you looked down from the upper stories of the building next door, a view he had often enjoyed because he was friendly with the concierge. The description on the museum's website is more prosaic: “The plan of the building resembled something akin to an inverted letter A, in technical terms a rhomboid, being shortest to the south (Euston Road) with sides tapering outward towards the longer end approaching Brill Place in the direction of Camden Town.”

Construction of the new library became controversial because of cost and sentiment. It took twenty years from the development of the original plans to the day of the Queen's ceremonial opening. During that time a series of builders' delays and price escalations frustrated the project and led to public grousing. Budgetary constraints resulted in a structure only two-thirds the intended size.

Years before when I first heard about the intention of relocating the library from the British Museum to a location that had been “a derelict goods yard immediately to the west of St Pancras station” I was one of the unhappy many. Thousands of serious scholars, including a number of American friends with readers' passes, had conducted research in the museum reading room. They lamented the change of an institution with such personal meaning to them.

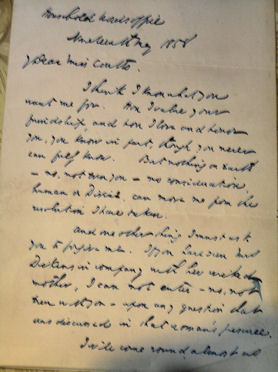

While never a scholar, my emotional tie to the museum library struck on my first visit to the manuscript cases, actually seeing the handwriting of authors I had read and even passed examinations on. Jane Austen and Oscar Wilde and Virginia Woolf and so many others. It somehow added a new level of actuality to all those books, the excitement of standing in the midst of an authenticity beyond my imaginings – ascension into English major's heaven.

How could soulless bureaucrats violate that sacred space? They did – eventually – and people in general, the vast majority, are happy with the results, the new British Library serving as one of London's most visited tourist attractions. And the manuscripts are there too, in different display cases, not looked down on from about, but mainly at eye level. Austen, Woolf, and Wilde, Joyce's Ulysses too, and so are hand-lettered Beowulf, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and Thomas Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur, works I didn't remember from my earlier visits to the British Museum. It may be that the new displays are actually easier to see.

Beyond literary works, the cases house illuminated manuscripts, Medieval Codices, a Guttenberg Bible, musical scores by Mozart and others, letters from scientists like Charles Babbage and Alfred Russel Wallace, and political figures like Gladstone, Florence Nightingale, original Beatles lyrics on scraps of paper in various childish handwritings (with headphones for listening to their performance), and an entire alcove devoted to the history and drafts of the Magna Carta.

The days I visited, racks displayed entries in a bookbinding contest to recover nominees for the previous year's Man Booker prize, leather of various colors and hand-tooled lettering. For the cover of a book on fish the replica of a fish tail and fish head protruded from the front. A bit over the top, some might say. But the general detail and workmanship celebrated the physical book as an art object on its own.

Visually, the literal centerpiece of the British Library is a six-story wood-framed glass tower holding the complete library of King George III that contains about 65,000 books and 19,000 pamphlets. While that king's sanity is questioned (as in The Madness of George III) and the American Colonies were lost during his reign, he did create the foundation of a national British library. There are worse legacies for a ruler.

The collection, of course, has expanded far beyond 65,000. According to the 2006 report, it houses close to 13.5 million books, more than three-quarters of a million serials, more than 8 million philatelic and 4 million cartographic items, 1.5 million musical scores, and many other objects. So what if it's shaped more like a rhomboid than a ship?

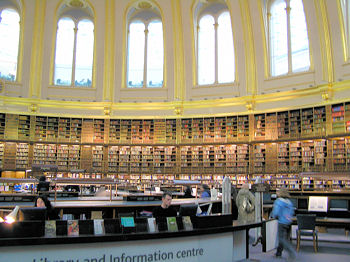

The British Museum, by the way, still has a reading room that focuses on books relating to the museum's collections, such as history, art, and travel. It's been situated in the middle of the Great Court since 1857 and still deserves a visit. That too was only a few minutes from our flat in the alley.

|

|

Dickens' House

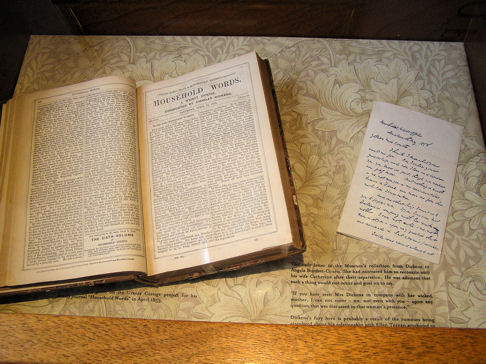

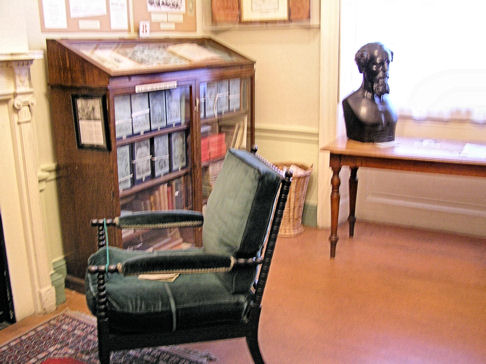

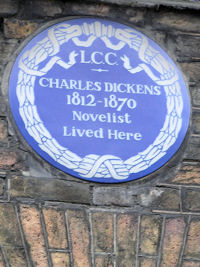

The building at 48 Doughty Street, in a long row of similar structures, was just one of Dickens' London homes, the only one turned into a museum with manuscripts, photos and paintings, original furniture, and various of his writing instruments. Dickens lived there briefly between April 1937 and December 1939, a young man, fresh from the fame and income of The Pickwick Papers and at the beginning of what turned out to be a most unhappy marriage to Catherine Hogarth. The explanations on the wall of one room reveal some of the details of that relationship, including his feelings for his sister-in-law Georgina and his later-years relationship with the young actress, Ellen Terry. Oh, those Victorians. The museum opened in 1925 after the house was threatened with demolition.

Woburn Walk

|

Just off Upper Woburn Place and a block from Euston Road, Woburn Walk was designed by Thomas Cubitt in 1821 as London's first pedestrian street. It's not very long, just a single block with bow-fronted buildings on either side.

|

|

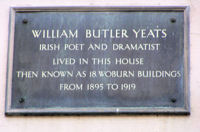

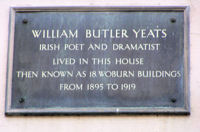

Though fashionable in its prime, Woburn Walk now seems to be in low-rent area, home to small shops and take-out places like Woburn Tandoori and Wot the Dickens. But W.B. Yeats lived on the street between 1895 and 1919.

Fitzroy Square

This quiet, attractive square in Bloomsbury contains the house, number 29, that was the home of Virginia Woolf from 1907 through 1911. George Bernard Shaw lived there first, between 1887 and 1898.

According to “Socialism in Bloomsbury: Virginia Woolf and the political aesthetics of the 1880,” an article by Ruth Livesey in the 2007 Yearbook of English Studies, Woolf rejected the pragmatic socialism of Shaw and Beatrice Webb, preferring instead the aesthetic socialism of William Morris. If that is so, Woolf's ideological disagreement certainly didn't affect her personal relationship with Shaw, at least, if we can believe what she told him in a typewritten letter of 15th May 1940. It begins, “Your letter reduced me to two days silence from sheer pleasure.” In fact, she confesses to having fallen in love with him (no doubt metaphorically) when they met at the Webbs' despite her intention to resist him. “But in a jiffy you made me re-consider all that and had me at your feet.” She notes that “you have acted a lover's part in my life for the past thirty years,” thus going back to 1910. And she extends an open invitation to visit her and Leonard in their home of the time at 37 Mecklenburgh Square. Perhaps they shared memories of living at number 29 – the efficiency of the fireplaces, the functioning of plumbing.

A number of other notables made their homes in Fitzroy Square: The Pre-Raphaelite painter Ford Madox Brown lived at 39. Roger Fry's Omega Workshop occupied 33, a design enterprise founded in 1939 by members of the Bloomsbury Group, including the artist and critic Roger Fry, Virginia's sister Vanessa Bell and her artist lover – after her affair with Fry – Duncan Grant, as well as Wyndham Lewis, who left early to set up the rival Rebel Art Centre. Grant had lived at 21 in 1909 before the Omega Workshop. William Archer, a theater critic and collaborator of Shaw's, at 27. More recently Ian McEwan made his home in the square and used it as a setting in his 2005 novel, Saturday.

One might think those London wanderings would have prepared me better if in a grotesque nightmare I had to retake all those Brit lit exams. But I'd probably read the questions and lose myself in daydreams of places, all those pictures in my head.

[copyright 2008, Walter Cummins]

|