|

an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins

|

|

Paris, Madrid, Florence, New York—Novel Collage

Essay by

|

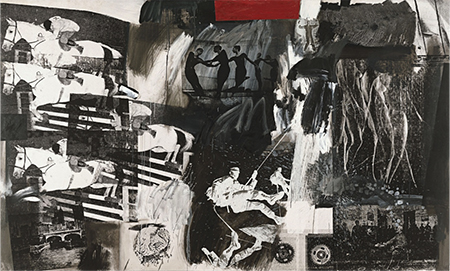

In Rauschenberg’s better known collages from the 1960s and 70s, we find any number of composite and association-laden images, and, again, I am proposing that these images’ arrangement and the artist’s layering, colors, and strokes of paint create a comforting illusion of balance, and thus also speak of the importance of balance (and not only to dancers, climbers, and horseback riders). Given various interjections above, and noting that Express is a work from the engaged 1960s, it is also hard to ignore its “politics.” As with the work of other “pop artists,” there is an Americana (and “art-i-cana”) feeling to Express; it’s a collection of images relating to our lives, our past, our art history, and these images are presented without analysis or criticism. We might say that Express—or Tom Wesselmann’s Still Life paintings, or Jasper Johns’s flags, Richard Hamilton’s Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, Andy Warhol’s Mao or Jackie Kennedy silkscreens—they express a wish that empty nostalgia could (like a time machine?) offer an escape, a way out of the present and of the human predicament more generally.

♦ Raymond Queneau Zazie dans le Métro (Gallimard, 1959).

♦ Émile Zola, L’Œuvre (Folio classique; Gallimard, 1983). Quotation and translated phrases are from a paragraph in chapter IV. The novel first appeared, in installments, in Gil Blas, 1885−86.

♦ It was, in fact, my old friend Marian Schwartz who first, decades ago, called my attention to this peculiar and much-enjoyed indulgence of travelers: reading books from their home countries. In Marian’s case, the indulgence has somehow connected to a more time-consuming (and, presumably, more deeply pleasureful) occupation: translating Russian books into English. Her recent publications include a new edition of Anna Karenina, Daria Wilke’s Playing a Part (a young adult novel with openly gay characters), and short stories by Mikhail Shishkin.

♦ Tom Lehrer, “The Folk Song Army,” as recorded on That Was The Year That Was (Reprise, 1965).

♦ Ben Aris and Duncan Campbell, “How Bush's grandfather helped Hitler's rise to power,” The Guardian, September 25, 2004.

♦ Bernard Bailyn, The Barbarous Years: The Peopling of British North America, The Conflict of Civilizations 1600-1675 (Vintage Books, 2013), 231.

♦ A used copy or two of Prudencio de Pereda’s Windmills in Brooklyn may be available from AbeBooks. The New York Public Library’s copy can be read at the Schwarzman Building of the library. Translator Ignacio Gómez Calvo and Hoja de Lata have produced a handsome and highly readable Spanish text.

♦ Where elsewhere I wrote about the Windmills story: Bad Marriage, Spanish Dancer, Zeteo, March 2016.

♦ The information on de Pereda comes from a biographical sketch prepared by the University of Texas’s Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, which is where de Pereda’s papers repose.

♦ The expressionist’s “whole dimension becomes vision. He does not look, he sees . . . The chain of facts no longer exists: factories, sickness, whores, shrieks, hunger. What exists at this moment is the vision of them.” Kasimir Edschmid (a German literary and social critic, 1890–1966), as quoted in Michael Hamburger, Modern German Poetry (Routledge and New York, McGibbon & Kee, 1962).

♦ Claude Lévi-Strauss, La pensée sauvage (Plon, 1962), chapitre premier.

♦ D.W. Winnicott, "Mind and its Relation to the Psyche-Soma" paper read before The Medical Section of the British Psychological Society, December 14, 1949, and

♦ David Litchfield, “The killer countess: The dark past of Baron Heinrich Thyssen’s daughter,” Independent (of London), October 6, 2007.

♦ One of the seminal critical texts about Rauschenberg’s work (among others) is Leo Steinberg, “Other Criteria,” an essay that began as a talk at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA),

March 1968. See Steinberg, Other Criteria with Twentieth-Century Art (Oxford University Press, 1972). This essay also gets on to the subject of noise, or modern noise. I quote:

♦ Portrait of Dante by Cristofano dell’

Altissimo (Florence, 1525-1605); part of the “Giovio Series” in Florence’s Uffizi Gallery.

♦ Robert Rauschenberg, 7 Characters: Individual, 1982. From a suite of 70 variations published by Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles.

♦ Rauschenberg, Express, 1963. In the collection of el Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

♦ Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937. In the collection of el Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid.

♦ Isabel Quintanilla, Cuarto de baño, 1968. In the collection of Javier Elorza.

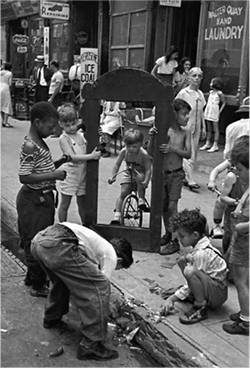

♦ Photograph by Helen Levitt, Untitled (Broken Mirror), New York, ca. 1940, silver gelatin print. This image is used on the cover of Molinos de viento en Brooklyn.

William Eaton is the Editor of Zeteo. A collection of his essays, Surviving the Twenty-First Century, was published by Serving House Books. For more, see Surviving the website. The present text is one in an emerging series of postmodern juxtapositions. In this regard, see from the Literary Explorer Bologna Postmodernism Bob Perelman Amis and from Zeteo: O que é felicidade (Corcovado, Kalamazoo).

“Napoléon, mon cul [my ass],” Zazie replies. “He doesn’t interest me at all, that stuffed shirt, with his fucking hat.”

Well, then, a visit to a bookstore—to Shakespeare and Company, or to W.H. Smith or Galignani, or to San Francisco and Berkeley Books (both near the Odéon). Instead of being overwhelmed by the sights, you could install yourself in a nice café with an English translation of any one of the many excellent French novels that offer their own tours of the city. Alexandre Dumas’s La reine Margot (Queen Margot) for the streets around the Louvre in the sixteenth century. Zola’s L’Œuvre (His Masterpiece) for nineteenth-century bohemians’ haunts—la rue du Cherche-Midi (before it became chic), the Batignolles quarter on the side of Montmartre, l’Île Saint-Louis, or “cette gaité vibrantes des quais, la vie de la Seine, . . . ” The dance of reflections in the current, the potted flowers in the seed merchants’ shops, the noisy cages of the bird-sellers, all the racket of sounds and colors along the banks of a great river (in the century before motor vehicles and airplanes).

But no, no again. If you’re like me, you’re going to end up with an American book, having decided that now—in the midst of this visit to Paris—now’s the time to re-read The Great Gatsby, Elmer Gantry, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, or, à l’extrême, U.S. Grant’s memoirs.

I am hardly the first to notice how traveling abroad can lead us back to our home countries, while and because we’re still far away. Here I am particularly focused on this habit that some of us have when traveling: of reading books not only written by authors from our own country, but books that are very much about our home countries. And, as shall be touched on below, this habit may extend beyond the books we read to art works that engage us or, say, to a movie that we might go see.

The American composer George Crumb’s string quartet Black Angels—an impassioned response to the Vietnam War—where did I first hear it performed? In Madrid of course. (And of course at la Fundación Juan March, Juan March having been a smuggler, corporate raider, etc., who was a major early supporter of Franco and of the military rebellion against the Spanish Republic—the Spanish Civil War. Rich before, he became even richer with the help of the fascist regime. Rich enough to have provided a venue for the presentation of wonderfully creative, beautiful squeals from losers, the Left? As the satirical songwriter Tom Lehrer put it, Franco may have won all the battles, but “We had all the good songs.”)

a dilapidated, half-built port village overrun with a floating population of idle, brawling soldiers, sailors aimless; pigs and other animals roaming the dirt streets. Trash of all kinds—rubbish, filth, ashes, oyster-shells, dead animal[s]. And privies built so that hogs may consume the filth and wallow in it.

Was I lucky to have escaped back to the Old World, la Fundación Juan March?

Ditching in my back pocket the map the hotel had given me, I sought to make my own way from la Plaza de España to a three-star cultural institution with ties to fascism: el Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. (The money here came from a German industrialist family, one of whose scions was a major early backer of Hitler. And, of course, too, it has been reported that, during the Nazis' reign, this scion had dealings with another: Prescott Bush, father and grandfather of the eponymous US Presidents.)

On a side street I spied a small bookstore, Sin Tarima Libros. Depending on context, the Spanish word “tarima” could be translated as “dais,” “flooring,” “platform,” “stage.” As Sin Tarima turned out to have a sister store, Con Tarima Libros, I am tempted to propose that this latter must be full of uplifting books, and “my” store, Sin Tarima, was for the out of step—the ἄτοπος (out of place), as Plato characterized Socrates. (I am told the Madrid chain has a third store: La Fugitiva.)

Meanwhile, Sin Tarima is a nice little bookstore of the old style; its two short aisles leave room for a browser or two to wander between the walls of books and the table tops piled with books in the middle island. My browsing had scarcely begun before I realized that I wanted a not long book that, my rudimentary Spanish notwithstanding, I could and would read. A book translated from English, and not Henry James.

I ended up with Molinos de viento en Brooklyn, a translation of Prudencio de Pereda’s novel (or memoir in the form of a novel) Windmills in Brooklyn. Published in 1960, the book is now out of print in English. The Web has subsequently informed me that de Pereda was born in 1912 in Brooklyn, to Spanish immigrant parents.

He was first encouraged to be a writer after reading Ernest Hemingway as an undergraduate Spanish major at City College of New York (1929-1933). He published his first story in 1936, and during the Spanish Civil War, met Hemingway. The two collaborated on the commentary for the films Spain in Flames and The Spanish Earth, espousing the Loyalist Republican [anti-Franco] viewpoint.

of European immigrants, grew up—was I trying to keep crossing and re-crossing the Atlantic without getting my feet wet?

I have written elsewhere about the story Windmills tells. What interests me here is the book’s cross-culturality. As the prose of Windmills at times suggests, de Pereda’s mother tongue was Spanish. And then, in Brooklyn, he grew up to write in English. And so now, in being translated into Spanish, perhaps his prose has found its true home? And was I—in reading in Madrid and in Spanish this book about my home town (New York) and the borough (Brooklyn) where my mother, the daughter/granddaughter

It can be said that our current mode of transcontinental travel, by airplane, allows us to do precisely that. And I once heard the director of a study-abroad program, for US university students, complain that the moment his students landed in Madrid, or Lagos, San José, Hanoi, they got on the Internet to rejoin their friends and pop culture back home. They were never immersed in a foreign country and language, rarely made to feel anxious or deficient, and thus also rarely learning anything new. But certainly I, and others who, abroad, search out books and read as I do—there is this sense in which we, too, resist inundation, or make sure to bathe daily in familiar waters, as if to rinse off or dilute the unfamiliar. To relax a little in the midst of our travels, we may call this.

face, to keep the world from entering “me,” and to keep me from merging with, disappearing into, the world. And to help me not recognize my or anyone else’s predicament.

It has been said of the Expressionists of a century ago that they did not look; they saw. I find this a way of saying that the Expressionists’ images came from within; their seeing involved an attempt to impose the personal on the world, in lieu of a recognition of how the world imposes itself on the personal. We might say that now, as tourists, we neither look, nor see; we record. We neither try to impose nor to recognize how we are imposed upon. We hold up a screen, an inter-

At their best, our travels involve us (without our realizing this) in the making of collages. On one level these collages are simply all the pictures we take. But there is also a subconscious collage of sights, sounds, texts, memories. Recent trips—or hours at home on the couch—ineluctably expand and re-arrange what we are making of our experiences.

Critics of present, “postmodern” ways have suggested that, in our current collage-making, we no longer seek to put present phenomena in context, be this context historical or otherwise. Not to jump the gun, but, for example, it could be said that nowadays we see no problem in putting Grant and Lee at Appomattox in the same frame as and right below a naked young woman coming down a staircase. Whether we are looking, seeing, or recording, what we are not doing is understanding. Or what we are doing is not trying to understand, or, rather, trying not to understand. And how helpful are our beloved screens! Keeping the world to such a manageable size—10 or 20 square inches—we might say it becomes too small to see.

A dark day, though not the only such. I was alone there where all agreed to make an end of Florence. Ma fu’io solo, la` dove sofferto fu per ciascun di torre via Fiorenza. Visiting the Uffizi, so many other tourists with their cellphones swarming from famous painting to famous painting. Miserere di me, qual che tu sii, od ombra od omo certo! Whether you be ghosts or real people, have pity on me. But no, my human form was at best an obstacle; the paintings went unseen; even the echoes of Dante’s inferno in the hellish scene—unseen and unheard.

into foreign lands and languages where, we fantasize, the too-familiar regimes, rules, and limits no longer apply. But then, abroad, the world may seem larger and more threatening than we like to imagine it. Our enthusiasm for the new and foreign may be challenged by a fear of losing not only beloved fantasies, but also our moorings, or let’s call this the particular frame in which we have been able to organize ourselves and give ourselves a central role. And thus we thank our guidebooks and websites for keeping us organized, identifying the good, what is important: the top 10 things to see and do, the Thyssen’s best paintings, where to eat, where to stay.

And thus the point I have to make—and as a result of having indeed seen a certain collage at the Thyssen museum in Madrid—may seem conservative, traditionalist, and Formalist (and elitist). My point is that our travels—and yet more than our lives back home?—threaten us with disorder and insignificance (our political and economic impotence included). We may be enthusiastic for the new and for escaping

Additionally, for artists, striving for order and perfection often connects, however tangentially, with ideas and feelings of beauty. Imagine a portrait of the museum founder Baron H. H. Thyssen-Bornemisza (as above). Not long ago, a racy book claimed that, in the waning days of the Second World War, one of his daughters gave a party for SS officers, Gestapo leaders, Nazi Youth, etc., at the Thyssen castle in Austria. As part of the festivities 200 Jews were slaughtered. Or—better?—imagine a Rorschach ink blot that, when we tilt our head one way, seems to make no sense at all, and, when we tilt our head another way, speaks all too loudly of things we would rather not think about. Artists (and writers) are at work in the middle, crafting illusions that are comforting in their orderliness. These comforts include works that may seem disorderly, iconoclastic, anti-savage-capitalism, or otherwise anti-establishment. Insofar as these works call attention to reigning cultural, political, and economic regimes, they strengthen our sense of structure and strengthen the structures themselves. More generally—with the help of frames, curators, museums, and other institutions—works of art oppose chaos. And for this we are thankful and pay the admission fees.

In the 1950s, the young Rauschenberg became famous for iconoclastic works—for his print of a tire track; for exhibiting his erasing of a well-known older artist’s drawing; for putting his bed up, vertically, on a gallery wall; monochromatic paintings; etc. Personally, I first “rediscovered” Rauschenberg in 1983 when he exhibited in New York a series of collages he had made in collaboration with paper makers in China. This series called my attention to quite another aspect of Rauschenberg’s art: his rare and complex sense of harmony. Perhaps “balance” is a better word. In the 7 Characters print reproduced somewhat far above, one can feel viscerally the weight of the bottom right, seemingly suspended element, and it may seem that the rest of the work strives to achieve a repose that this weight cannot throw out of kilter.

Since I was in Madrid, I had an opportunity, at el Museo Reina Sofía, to see Picasso’s Guernica, which is, inter alia, a visually harmonious work, but of a different sort than Express—and not only because of Guernica´s anti-war message and passion. In Guernica, there is strong movement—in the turn of heads, the striding of a central figure, the reaching of another—toward the left side of the canvas. This movement is highlighted by the desperate figure alone in the upper-right-hand corner, arms outstretched. We may note, too, that war is an example of how destabilizing and unharmonious movement can be. Masses of people, savage businesspeople included, are propelled to surge in one direction or another, clashing, killing, and destroying.

In contrast, Rauschenberg’s collages—for all they may include pictures of movement and there may be movement in the brush strokes—they are static. Without wishing to undercut the warmth of Rauschenberg’s work, I will use the expression “frozen in time.”

A viewer may be more immediately struck by the specific images Rauschenberg has chosen to silk screen. Express seems to be about something, even something obvious—movement? dance? something about history or about art history? (Muybridge’s and Marey’s stop-motion photos? Duchamp’s Nu descendant un escalier − Nude Descending a Staircase?) There is certainly plenty of history in this collage. And yet, what I am suggesting is that all this stuff is a kind of tease; the work is not about the now, but points toward a timelessness, specifically toward the timeliness of artistic and human values—toward our need for and appreciation of harmony, balance, order (and for a kind of silence or stillness that they may bring?).

or Order, goddammit!—and the particular chaos of our present moment. And perhaps on some level (in his subconscious?) Rauschenberg understood, too, that, in order to achieve order, he would have to make the connections between the images purely formal or visual, independent of history, politics, human striving.

The Thyssen includes a Rothko painting, Untitled (Green on Maroon), which is also a harmonious wonder, as is a Moholy-Nagy work of two half-circles arranged perpendicularly (English title: Circle Segments). But you might say that Rauschenberg set himself a more complex challenge: finding or imposing harmony and repose on such an assortment of images and associations. He seems to have understood both the demand we make on artists—Order, please;

In the first months of 2016, the Thyssen has featured an absorbing temporary exhibition of work by post-World-War-Two Madrid artists who have been considered realists. I believe the reproduction above, of one of the most beautiful of Isabel Quintanilla’s paintings, will suggest why this label “realistas” has been attached to these artists. However, I would propose that, as exquisite as these artists’ work is, it is hardly as realistic as Express (or Guernica).

The Madrid artists’ works, even their street scenes, tend to be devoid of human beings and quite simple in their composition. Beautiful order and perfection are being achieved through an escape from reality. The paintings and drawings satisfy a wish that, in or through familiar interior and exterior spaces of the “real world,” we might escape the real world. From this perspective, we can see the greater ambition of Rauschenberg’s collages, which seek to impose order—or quiet—on more complex, disparate phenomena. Quintanilla’s 1968 Cuarto de Baño (bathroom), draws the eye to two centers—two possibilities, let’s call them—the shelves and the laundry (and the bag of cotton pads for make-up removal, just slightly titling the painting rightward?). Rauschenberg’s Express is notable for having six centers—horse and rider, ferry terminal, dancers, rappeller, nude, Grant and Lee—that compete for our attention. And if some of these images or people are on top, some brighter and some more somber, they seem equal at least in their black-and-white, silk-screened superficiality. (And, thus balanced, they deny hierarchy, which plays such a large role in our lives and in our ordering systems?)

Like bees deranged by pesticides, the Uffizi cellphone picture-takers flitted from masterpiece to masterpiece, no longer able to find any honey. And, I can assure you, most of the photos that were taken have been, at best, swiped a few times and then left in clouds, in storage—any honey ignored. (But perhaps people’s expanded capacities for recording, and for recording rather than looking or seeing, save them from regret? Or regret—intimations of mortality—is reserved for what we have not had enough time to photograph and for technical problems and oversights? “My daughter scored the winning goal, and I didn’t realize my phone had turned off.”)

I hope and trust that the present piece has suggested that there remains another, vastly more challenging way to live. I would like to also propose—and now pointing the way toward some future piece—seeking and exploring, however awkwardly, confusedly, the connections and disconnections—the familiar amid the foreign, the foreign amid the familiar, the savage amid the bourgeois. Yes, challenging, and more engaging (should that remain, for a few, of interest).

Notes

published in The British Journal of Medical Psychology XXVII, 1954: 202-03.

♦ Ma fu’io solo, . . . and Miserere di me, . . . are from La Divina Commedia di Dante Alighieri, the first quotation from Canto X and the second from Canto I. English translations appear in the text above, before the first of these lines and after the second one.

When in the early 1960’s he [Rauschenberg] worked with photographic transfers, the images—each in itself illusionistic—kept interfering with one another; intimations of spatial meaning forever canceling out to subside in a kind of optical noise. The waste and detritus of communication—like radio transmission with interference; noise and meaning on the same wavelength, visually on the same flatbed plane. . . . What he [Rauschenberg] invented above all was, I think, a pictorial surface that let the world in again. Not the world of the Renaissance man who looked for his weather clues out of the window; but the world of men who turn knobs to hear a taped message, “precipitation probability ten percent tonight,” electronically transmitted from some windowless booth. Rauschenberg’s picture plane is for the consciousness immersed in the brains of the city.

♦ E.M. Forster, Howards End (1910), chapter 22. Appropriately, I have, and like many another, divorced the “only connect” line from its context. More of the passage:

Mature as he was, she might yet be able to help him to the building of the rainbow bridge that should connect the prose in us with the passion. Without it we are meaningless fragments, half monks, half beasts, unconnected arches that have never joined into a man. With it love is born, and alights on the highest curve, glowing against the gray, sober against the fire. . . . Only connect! That was the whole of her sermon. Only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its height. Live in fragments no longer. Only connect, and the beast and the monk, robbed of the isolation that is life to either, will die.

Art works reproduced above and at right

[copyright 2016, William Eaton]