|

an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins

|

MIAMI DAYS:

POETRY, STELLA, ART, FOIS GRAS, ALE,

CIGARS, BOOKS & BOOKS & THE BETSY

by Thomas E. Kennedy

Unless otherwise indicated all photographs are by Jessie Vail Aufiery—the hotel art was kindly provided by the Hotel Betsy and the book cover is from the original 1959 edition.

Out of my life I fashioned a fistful of words

When I opened my hand, they flew away.

—Hyam Plutzik

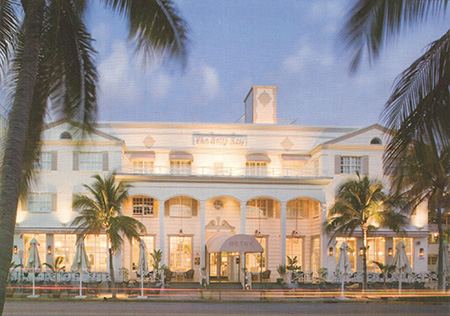

I am not familiar with the poetry of Hyam Plutzik before I begin my week in residence in The Writer’s Room at The Betsy, a luxurious hotel on Ocean Drive in South Miami Beach (TheBetsyHotel.com).

I. The Betsy and the Poet

%20001.jpg) |

After I check in and locate my room on the ground floor, the door amid a gallery of

Bob Bonis photographs of the Beatles and Rolling Stones on their 1960s tours, I find on the desk, along with a letter of welcome on gold-bordered vellum, a copy of Hyam Plutzik’s Apples from Shinar, reprinted by Wesleyan University Press from the 1959 edition on the centennial of the poet’s birthday. A gift. With an afterword by Yale literary scholar David Scott Kastan.

Hyam Plutzik, I learn, was a name included among the great mid-century American poets—Theodore Roethke, Richard Eberhart, Howard Nemerov, |

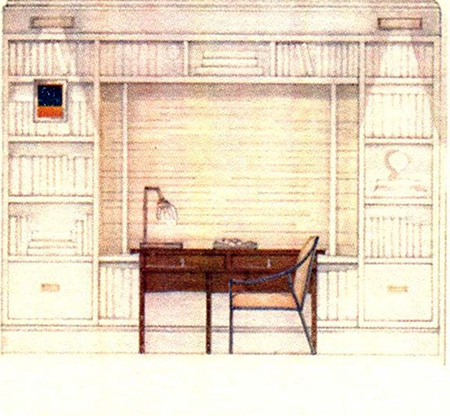

Moreover, the book is resting on the desk at which Plutzik wrote his poems, taken from the basement of his home in Rochester, New York, where he was a professor at the University. Alongside the Plutzik collection is a sturdy envelope addressed to me with a DVD— Hyam Plutzik, American Poet — as well as, beside it, a copy of Harold Robbins’ The Betsy. There is a self-ironic sense of humor at play here. Flanking the desk are two tall bookcases containing, inter alia, volumes by Hayden Carruth, Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes, James Tate, an Ann Charters book of photos and biography of the Beats… (Every room in The Betsy includes a shelf of ten or twelve books.) Also on the desk is The Betsy newsletter with a color picture of myself and a bio note under the words “In Residence in The Writer’s Room…” and a bookmark, embedded with wildflower seeds: “Use it to mark your place or moisten it thoroughly, plant it in soil, and watch the wildflowers bloom.” On the obverse are printed the Plutzik lines,

The abrupt appearance of a yellow flower

Out of the perfect nothing, is miraculous.

Hanging on the luxurious walls of the room are framed Plutzik lines. The letter of greeting tells me I am welcome to help myself to the minibar, to the snacks, to dine in the hotel restaurants, to drink in the lounge, to enjoy the hotel’s outdoor pool, or the white sand beach just across the street . I have seldom in my life felt quite so welcome. The letter is signed by the hotel chairman, the general manager, and the vice president for philanthropy, the former the third child of Plutzik, Jonathan, the latter the fourth daughter, Deborah.

I consider watching the DVD, but it is past 10 pm, and I would like to catch the rooftop lounge before I sleep. On the roof, across Ocean Drive from the Atlantic, I sit at a table, gazing out onto the dark ocean night and a dented orange moon in the velvet sky, a chill bottle of Stella Artois at my elbow, breeze off the ocean drying the sweat on my face, and leaf through Apples from Shinar.

Before I rode the elevator four floors to this roof, I quickly googled at the hotel desk computer (also at my disposal) “Shinar,” because I hadn’t a clue: Shinar was a biblical location in Mesopotamia, perhaps from the Hebrew for two rivers or two cities: the Tigris and Euphrates, or Uruk and Babylon.

There’s no title poem in the book to give a hint. The hint must be in the title itself. Perhaps we’re talking the birth of civilization here. Gilgamesh and Uruk. Shinar also enclosed the plain that became the Tower of Babel, so we’re also talking language and communication and the failure to communicate, too. Or maybe we’re talking Eden, the forbidden fruit? Apples is plural, however—maybe apples stand for the poems themselves, the fruit of willfulness, awareness, self-consciousness, the will of human beings, the naming of things?

The young woman behind the bar comes over to my chair on the lip of paradise and asks if I’d like another Stella. If her name is Eve, Eva, or Evelyn, I think, I’ll bite her, but she might not understand, so I simply say, “Yes, thank you.” I read the Afterword by David Scott Kaplan first: “In the 1950s Plutzik was clearly recognized as among the generation of poets claiming the mantle of Frost and Jeffers, Stevens and MacLeish.”

Louis Untermeyer and Stanley Kunitz served as the jurors for the 1961 Pulitzer, but it seems that Plutzik was also short-listed in 1950 and ’60, too. Ted Hughes spoke of Plutzik’s visions as “authentic and piercing, and the song in them is strange – dense and harrowing, with unforgettable tones. The best of his work seems to me marvelously achieved, a sacred book.” Born in Brooklyn in 1911 to recent immigrants from Belarus who soon moved to a farm near Bristol, Connecticut, Plutzik won Yale’s highest award for poetry in 1933 and again in 1941, the only person ever to win twice. He also won the Yale Younger Poets Award in 1940.

I remind myself, here on the roof beneath the dented orange moon, that I am reading secondary opinions and facts. Go to the poems themselves:

As the great horse rots on the hill…

till the stars wink through his skull;

As the stars become husk and radiance…

Thus you prepare the future for me and my loved ones.

And,

Trying to imagine a poem of the future,

I saw a nameless jewel lying

Lurid on a table of black velvet…

Then one said: “I am the poet of the damned.

My eyes are seared with the darkness that you willed me.

This jewel is my heart, which I no longer need.” And,

a great stag came out of the woods,

Broad-antlered, approaching slowly on the moonlit field,

And looked around him like a king and re-

entered the dark.

By one a.m., I am sated with eating poetry and sipping Stella, am in bed, eyes closed to the great flat screen at the foot of the bed, dropping off to the babbling nonsense of Fox News.

II. The View and the Exam

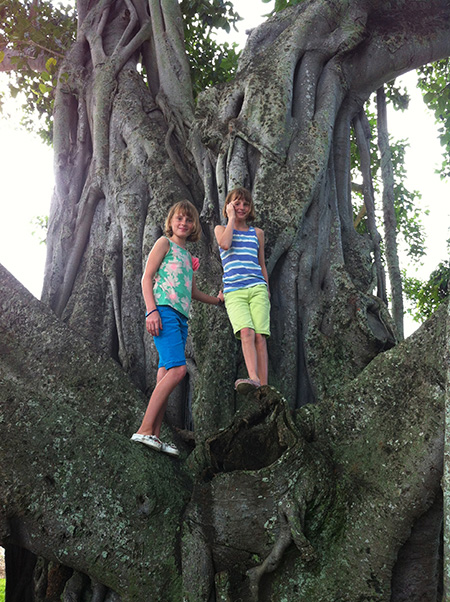

Today, I am dining with my hosts in north Miami – the woman who organized my stay at The Betsy: the writer Jessie Aufiery and her husband Walter, from Paris, and their twin daughters, 11-year-old Chloe and Mira, and Jessie’s father, the painter Dennis Aufiery and his wife Carol. Jessie and Walter and their daughters had lived in Paris for the past many years, before that in Manhattan.

Jessie picks me up at The Betsy and drives north over the bridge across Biscayne Bay to their 79th Street high-rise. The apartment is comfortably sized, but leads onto a broad balcony with an astonishing view. The photograph that I have does not do it justice. It includes Biscayne Bay and the bridge and, further to the south, the Atlantic ocean – a dizzying, glittering expanse of sea. Literally I cannot take my eyes off it.

Jessie’s husband Walter is a tall, slender man of about forty and offers fois gras at the table on the balcony with a glass of red which could only have been chosen by a Frenchman. Nibbling goose liver and sipping burgundy, trying not to be hypnotized by the view, I remind Chloe and Mira that they have promised to show me their sketchbooks. They have just been admitted into a school that runs from sixth grade to twelfth for gifted students of art. The entrance exam consisted simply of their sketching for about an hour; after fifteen minutes they were admitted.

They show their sketches, first the one, then the other: the one not showing touches the shoulder of the one showing, their spirits clearly connected. Their sketchbooks are definitely influenced by their artist grandfather, Dennis Aufiery—studies in still lifes, gradation of shadings, sketches of hands, faces… The girls’ slender faces contain the direct, steady gaze of artists.

Suddenly it occurs to me that this talent, unlike the tendency to conceive twins, would not likely skip a generation. I’ve always thought of Jessie as primarily a writer since the first time I met her—when, as judge of a short fiction competition, I picked her story for top prize. (It was good that I didn’t see how beautiful she was before I picked – this way, I could honestly say I hadn’t even seen her before she won!)

Now, I ask, “Jessie, do you paint as well?”

“Not really,” she says, but reluctantly produces a portrait of her father that is excellently rendered—his squared jaw, his nose, the blue of his eyes.

“That portrait is good, I think,” Dennis says and then asks, “Say, do you know which ankle bone is higher? Right or left side? Don’t look now!”

I didn’t even realize that we had two ankle bones on each ankle, but it makes sense. Whatever it is, it turns out I’m wrong, and he asks, “How many times can the length of your foot fit up your calf?” And, “How many times will the length of your hand fit up your forearm?”

Wrong every time, but it comforts me to know that there is this unapparent symmetry to human anatomy. It also comforts me to know that a writer doesn’t have to know that symmetry—all a writer has to know is that an artist has to know it.

As we come in from the balcony to dinner, I notice that there are four framed 6” x 9” oil paintings ranged along the sofa, propped up face out against the back.

“Pick the one you want,” Dennis says.

Although I never met him before, he knows that I have long admired his art.

“You don’t have to pick now,” he says. “You can eat first and think about it.”

But I know that if I have much more wine, I will not be fit to pick. From my place at the dinner table, enjoying beef bourguignon and more burgundy, I can see the four paintings on the sofa and glance up from time to time, sensing that it’s an examination: what I pick is what I deserve.

A few hours later, again out on the balcony, I notice it is nearing midnight. Some of these people have to work tomorrow. Dennis has gone to bed. Carol is still up, as are Jessie and Walter. Chloe and Mira have hugged me goodnight, warming my heart. Carol is reading one of my books, but exhorts me not to tell her the ending. “Is it happy?” she asks. “Don’t tell me, don’t tell me!”

“I really have to get back to the hotel,” I say. Jessie phones a taxi, and I decide that when I go into the living room, I will pick the painting Zen style: just quickly pick. Before the sofa, my eye goes first to the one on the far right, then bounces to the far left, and I pick that one. Holding it, I hear Carol and Jessie call out in unison, “You picked the best!”

(Now, as I sit on my red sofa in my tiny living room in Copenhagen, I look across to the painting, its red impressionist lighthouse, across a choppy aqua and black with dashes of coral strait, beneath a sky of patchwork color, over a colorist jut of earth, I agree. I chose the best. I passed the exam. The painting fits in among the dozen colorist paintings and lithographs on my wall.)

III. Books & Books and Wynwood Walls

Last night I did my reading at Books and Books in Coral Gables, a fine experience in an expansive bookstore of squared wings around a courtyard bar which we end seated in over several glasses of wine. The book store live-streamed the reading, and it can be viewed on new.livestream.com/uainmedia/thomas-kennedy and copies of my back titles were ordered for the event. Afterwards I signed many copies of Kerrigan in Copenhagen, and they will be distributed to the various Books & Books shops.Margie, the mother of my friend and colleague, novelist David Grand, attended the reading with David’s stepdad, Joel. Margie is a lovely woman. She came from Middle Village, Queens, where I had a girlfriend in 1964. Did she know Dry Harbor Road? She did.

I take advantage of the opportunity to give Dennis a copy of the new novel I am reading from, Kerrigan in Copenhagen, as a token of thanks for his painting. A couple who came to the reading and joined us for drinks, the poet Letisia Cruz and the fiction writer Bob Beaird, suggest that my stay in Miami must include a visit to Wynwood.

Jessie collects me in her Audi late next morning, and we follow the directions of her GPS tracking device north to Wynwood. She explains that Wynwood was previously a slum but the artists have moved in and, as will happen, mounting real estate prices and gentrification followed them. It is still not quite gentrified, however.

When the massive, low walls of the buildings on the broad roadways and streets suddenly are adorned with ornate graffiti, I realize we are there. Graffitti is not the word; these are composed and breathtaking, giant figures amidst intricate geometrical designs of colored spectrums.

Our first stop is the Wynwood Kitchen and Bar (wynwoodkitchenandbar.com) on NW 2nd Avenue, where we meet Letisia and Bob. Letisia, she says, is reading my novel, and over the first, very spicy bloody Mary, she says, “I have to know, is the ending happy?”

“I don’t want to spoil it for you.”

“I have to know if it’s happy, that’s all. Not details.”

“Sort of.”

Letisia fits well into Wynwood. The whole length of her arms, including the shoulders and upper back, are decorated with tattoos: On the right arm is a girl holding a bluebird in her hand; her body grows out of a dandelion, and she is wearing a purple dress, her black hair, adorned with a red rose, metamorphosing into birds (that part is on Letisia’s shoulder and upper back, visible above her tank top). A flower is inked on her left wrist, another flower on her forearm, both red, and a small bow and arrow decorates the inside of her upper arm.

Born in Cuba, Letisia moved to the U.S. as a baby. Bob is of Mexican descent but grew up in Michigan. When they first met, Letisia teased him, asking, “What’s with this ‘Bob,’ Roberto?” But his real name is Robert, and he’s called Bob and speaks standard Midwestern. After thirty years in Copenhagen, I have more of a foreign accent than Letisia, who speaks flawless American as well as flawless, as far as I can tell, Spanish.

After a few spicy bloody Marys and a brunch of questo frito, medjool dates, pork belly and some kind of spiced spinach on the back patio of the restaurant, surrounded by walls of art of Logan Hicks, Ron English, Ryan McGiness and many others, including a large graphic shark mouth by Kenny Scharf, we stroll alongside, among the Wynwood Walls (thewynwoodwalls.com).

(Art by Stelios Faitkas of Greece; photo by Bob Beaird)

Bob snaps a photo of me flanked by Jessie and Letisia in front of the first mural, a huge blond woman in skimpy underwear, lofting a phallic missile. The women in the photo look delightful; however, I look rather like Tony Clifton, Jim Carrey’s decidedly unpleasant, Vegas crooner alter ego as Andy Kaufmann in Man on the Moon. There are many other photos of huge murals on the Wynwood Walls and outside – a woman touching her lips and one, smaller one (visible only at certain angles) looking through her interlaced fingers (by the Australian artist Rone), a sixty-foot-long Lost Lover with a central golden figure (by the artist Faith47), another of a woman floating colorful images out of her eyes (by the Argentinian artist Ever)…

We stop in Panther Coffee (panthercoffee.com) for refeshments of cake and strong beer, the Wynwood Cigar factory on NW 24th St.—it, too, has murals—where I purchase three Edgar Hoill robustos, two to be shared by Bob and Letisia and Jessie and myself, one to be sent home with Jessie for Dennis Aufiery, who kindly provided me with a Cohiba the night before.

We end the day passing robustos and drinking half-quart cans of Dale’s Pale Ale at the back of Lester’s on NW 2nd Ave (Lestersmiami.com), and we have one of the best conversations of my life – if only I could remember it…

If these lesser things are subsumed within the Good—

IV. The Pen and the Film

My last day at The Betsy is bright with sun and a pure blue sky, and I decide to take a chaise lounge on the beach and jot notes of my visit. Clipped to my shirt pocket is my Montblanc, the ballpoint with which I’ve written the first draft of the most recent dozen of my books. The young woman in the beach shed provides a large white towel, and the young man hurries out to set up a chaise lounge for me, covered with a fitted terry cloth sheet.

At one point, Jessie must have driven me back to The Betsy because I find myself atop the rooftop, sitting in a chair at a table against the rear wall. The moon above me is no longer dented – it is full and bright, orange as a cat’s eye regarding me, and I am sipping a Stella and reading lines of Plutzik by its light:

These corrupt shapes: desk, mirror or tree –

The falsely transliterated, strangely planed

Creatures of eyesight and the sentient bones

(Themselves in the web of the spider), then all times

Are poses of the one actor, Time…

And still it is hot noon on the sea Tethys

Where the protoplasmic slime begets Aphrodite

Whose belly is history till the moon falls…

It is hot beneath the yellow sun, and I take off my shirt and toss it on the lounge to wade out and dive into the aqua blue water of the Atlantic. The water is womb warm, and I swim until my muscles are agreeably weary and my hunger has been stoked to visions of shrimp cocktail on the rooftop with a Stella Artois in which to swim the crustaceans.

I thank and tip the young man and young woman. By the time I cross the road to The Betsy my swim trunks are already dry, and I ride directly up to the rooftop, order a Stella and shrimp big as large crayfish. And while I wait I think to jot a note and reach to my shirt pocket for my Montblanc where I always carry it. It is not there.

Aside from the value of the pen (it cost $350), it sat with such balance in my hand, awaiting the inspiration of language, and I am attached enough to it that I am blinded with anxiety at its loss, even while trying to reason that it’s only a thing. But it is truly a cherished thing!

Calling to the barmaid that I will be back and to watch my things, I ride the elevator to the lobby and jog across the road to the pathway that leads to the beach, my sandals flopping beneath my feet.

“Did you see a black Ballpoint pen?” I ask at the beach hut, trying to quell the panic in my voice.

The young woman smiles. “You want pen?” she asks, handing me a disposable gray

plastic ballpoint.

I dash down to the chaise lounge I used and search the creases and folds of the mattress, but it is not there. I stand disconsolately on the beach, as unhappy as if I’d just lost my passport, my wallet, unhappy as if I’d just lost my identity. I truly valued that pen.

Out of the corner of my eye in the white sand, I glimpse a speck of familiar shiny black and jump for it. About to be swallowed forever by the hot, white sand is my Montblanc!

Looking around for someone to whom to explain how happy I am, how elated with relief, I realize that this is a moment I cannot share with anyone. Who will understand, who can understand? I am alone with this elation.

The last act of my day, I decide, will be to watch in my room the 2006 film about Hyam Plutzik—Hyam Plutzik, American Poet, produced and co-directed by the Academy Award nominated Christine Choy with her daughter Ku-long Siegel. Literary advisor to the film was Ed Moran. I fit it into the DVD player and have a cold Stella at hand, my Montblanc with which to take notes.

Many of the things I have noted in this essay are related in the film, many lines from Plutzik poems are read by Donald Hall, by Hayden Carruth, Stanley Kunitz, Galway Kinnell, and by Plutzik himself (he sounded rather like Lawrence Ferlinghetti—or should I say that Ferlinghetti sounded rather like Plutzik?)

But the film also tells how Plutzik went into World War II, into the Army Air Corps, in 1942 and served until the end of the war, how he wrote a poem about the ten crew members lost in an American bomber that was shot down, how he wrote a poem entitled “Hiroshima.” The film tells about how his first language was Yiddish, about his determination to be a poet, about his determination to “merit the respect of intelligent men.” It also tells about how he took on the “conventional” anti-Semitism of T. S. Eliot in “For T.S.E. Only,” and how unpopular that was in those days, in that place, how accepted was the anti-Semitism of Hemingway and Eliot and Pound and their peers. He did so compellingly, without embarrassment, implored “brother Thomas…” “Thomas, Thomas” to “weep together for our exile,” ending, “You hypocrite lecteur! Mon semblable! Mon frère!” And this was in upstate New York, a bastion of Republicanism, supportive of the Army McCarthy hearings.

The film also tells about his family— his children, his sons Jonathan and Alan, his daughters Roberta Plutzik Baldwin and Deborah Plutzik Briggs. And especially about his wife,

Tanya.

She relates how in the few years before his death, on January 8th, 1962, he was becoming more known and how she listens to recordings of her husband reading his poems: “That’s one of the most important pleasures I have.” About how, although he served his country during World War II, he would surely have been opposed to Vietnam.

But most remarkable is the way the film ends. Tanya Plutzik has been reluctant throughout the filming to allow the film-maker into Hyam’s study in the basement, but she finally consents. It is a modest place, a few bookshelves, a small window at the top edge of the basement wall.

The camera makes a round of the study, and then Tanya says, “I’m done. Are you done?” And the brief remainder of the film shows her from the back, slowly climbing the basement stairs, while her husband recites:

But feel the brush of the wind on the face, the bath

Of light, the torment of beauty deep in the throat

And strive in secret, this brotherhood so small,

To climb the stairway out of the dust a moment

Before the lying down to sleep and the surrender.