|

an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins

|

READING TOM SAWYER:

A SHARED EXPERIENCE

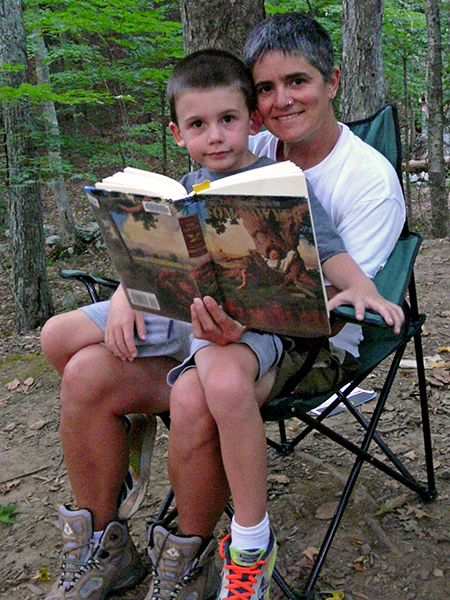

Essay and Photographs by Elizabeth Jaeger

Before bed, my son cuddled up next to me and after a brief introduction to Tom Sawyer, I started to read. Within moments, the memory of my first encounter with Tom Sawyer accosted me and I shook my head at the recollection, the reminder of how much I once despised reading. I must have been in early middle school when my teacher assigned a chapter for the class to read in our textbooks. She didn’t bother with an explanation of the characters or bother to inform us that what we were about to read was an iconic scene written by a famous author. She simply wrote the page numbers on the board, with instructions that we needed to complete the follow-up questions at the end of the story. Ugh! I remember groaning aloud. I groaned a lot back then when it came to reading, for I believed that the purpose of reading was to be able to respond to boring pointless questions that bore no significance on my life as a whole. And so I didn’t read. Instead, I jumped to the questions, tackling them one at time before scanning the text for the appropriate answer. I never answered the questions in a satisfactory manner, but I didn’t care. I just wanted to be done, and so I missed out on the real purpose and pleasure of reading.

behind stacks of books collected through the years, I have a copy of my own, a copy that once belonged to my father, but that copy, geared towards an older audience, has no pictures. My son, while having graduated to listening to chapter books with more words than pictures, still enjoys some illustrations in the books we share. If I was going to succeed in my attempt to make Tom Sawyer fun and exciting, I knew I needed pictures to help ground his attention in the text.

For years, reading was a chore—a brutal, boring, torturous aspect of my life. School had taught me that reading was about the destination, not the journey. When you read for school, most teachers demand that you prove your ability to comprehend a specific story by passing a series of exams. Because I have a poor memory, and because I struggle with tests, upon entering school, I quickly lost interest in the books that I used to love as a small child. And maybe that love of literature that my parents had tried so hard to cultivate when I was little would have been lost, had I not been such a social outcast in school. Towards the end of middle school the boys bullied me mercilessly because I was a tomboy. I was excluded from parties, conversations and get-togethers. Tired of being alone, I looked for companionship elsewhere and eventually found it within the pages of books. It was then that I stumbled upon my dad’s copy of Tom Sawyer. Disconnected from school, assignments and teachers, I finally discovered that the purpose of reading was the journey, the passage through time and space and the ability to escape real life. Reading, ironically, made school—at least the social aspect of it—bearable.

By the time I was a junior in high school, I had risen through the ranks of the tracking system. Instead of taking regular English, I enrolled in the honors class. My parents initially cautioned me against it. It is not often that one goes from nearly failing a subject to excelling at it in a year’s time. But I ignored their concern. That year I read Huck Finn for the first time. My teacher, Mr. Paccione loved that novel and his passion was infectious. He spoke about Huck as if he were a close cousin, someone to be idolized and respected. If he spoke of Twain’s aversion to racism, or if he addressed the N-word, I have no recollection of it. I only remember him telling us that Twain wanted to write a novel about the south, an honest account of life after the Civil War and that Huck embodied much of what was good in humanity. Huck wasn’t perfect, but perfection wasn’t exactly realistic. In that semester, much to everyone’s surprise, I earned an A. Literature was no longer simply an avenue of escape, it opened a whole new world of opportunity and discovery

Nearly two decades later, my role reversed. Instead of the student, I was the teacher, assigned to teach freshmen English in Plainfield, New Jersey. When I found out that I would be teaching Huck Finn I was ecstatic, but my enthusiasm quickly wilted. I spent a couple of days introducing the novel, Huck Finn. We talked about the historical time period and Twain’s motivation for writing a story that started out as a sequel to Tom Sawyer but eventually became a commentary on American prejudice. Few students took notes and when I read the first few chapters aloud, my predominantly African-American class nearly erupted into a riot the first time we encountered the N-word. One student called me a racist. Barack Obama had recently been elected president, and that student told me that he would write a letter to Obama demanding that Huck Finn be removed from the curriculum. I encouraged him to do so—it would be good writing practice—but as far as I know he never did. For over a month, I fought against the current of active disinterest and I lost. I never assigned reading for homework, it seemed futile. The students refused to read. I tried to persuade them with promises of discussions in lieu of tests but discussions about a boy to which they refused to relate held no appeal. By the time we finished the novel, their lethargy had extinguished my passion. I loved Twain, but after four weeks, my students had successfully driven my enthusiasm into a state of dormancy. Except for a brief interlude when I was in high school, it seemed literature and school were a lethal combination. One could teach it in school and maybe even learn about it in school, but to truly love and embrace it, one needed to experience it elsewhere.

And a campsite was nothing like a school. So after toasting—or torching which is far more exciting for a young boy—marshmallows on the open fire, my son and I withdrew to our tent. Tucked into his sleeping bag, my son curled into my arms and by the light of a small red camping lantern, I read him a chapter of Tom Sawyer. English has changed slightly since Twain’s day, and so the language in places was a bit dense and difficult for my son to understand. When his eyes clouded over in confusion, I’d pause in the narrative to explain the plot and we’d talk about why Tom often behaved like a delinquent.

In the morning, on the last day or our camping trip, we rose early in order to take a detour to Hartford before returning home. I had some trepidation that my son would find the visit boring, but pulling into the parking lot he pointed up the hill and asked, “Is that his house?” In his voice, a touch of excitement rang out and I hoped that it would translate into enthusiasm on the tour. Stepping into the welcome area, a life size Lego Twain greeted us. My son loves assembling Legos and seeing them he shrieked, “Is that all Legos? I want one!” After explaining that the Legos weren’t for sale, he mimicked Twain’s pose and smiled for a picture.

“Samuel Clemens and Mark Twain are the same person,” the tour guide clarified. Disappointment morphed into confusion as my son processed his response. “Mark Twain is Samuel Clemens' pen name. It is the name he used when he wrote his books.”

I paid for my ticket and the tour guide handed my son a sheet of paper on which were pictures of items he would see inside the house. The mini-scavenger hunt would occupy his attention, and hopefully keep him engaged. The tour started when the tour guide announced, “Many of you are familiar with Mark Twain, but today I will speak about a man named Samuel Clemens.”

My son’s shoulders sagged, his brow wrinkled and his mouth settled into a determined frown as he turned to me. Clearly disappointed, he asked, “But who’s he?” The tour guide chuckled as I silently berated myself for leaving out that one key kernel of information.

“Oh,” my son shook his head, “That’s too confusing. I’m just going to call him Mark.”

Inside the house, I was surprised but pleased with my son’s behavior. He listened intently to the tour guide as we moved from room to room. He was intrigued by the fact that Mark Twain was a father, and when the tour guide spoke about how Twain would tell his daughters stories based on objects placed over his mantle, my son looked at me and said, “That’s what you do. You tell me stories.”

“Yes,” I laughed, pleased to be compared to such a great writer, “Only mine aren’t quite so famous.”

As we moved through the house, my son checked off the items in his scavenger hunt, determined to get them all so that he might claim his prize at the end. In the billiard room, as he was checking the box besides the painting he located on the ceiling, the tour guide pointed to a table in the back corner of the room. He explained that it was while sitting at that table Twain penned his most beloved and well known stories, including Tom Saywer, Huck Finn and The Prince and the Pauper.

The title clicked, my son’s jaw dropped and his eyes opened wide as he gaped at the table. “There?” He said. “The book I’m reading, he wrote there?”

“Yes.” I said, thrilled by his obvious excitement.

Launching his hand into the air, he waited patiently for the tour guide to acknowledge him and when he did, my son exclaimed, “I’m reading Tom Saywer.” In that moment, the author and his book were transformed into something both intimate and special. My son walked away from the tour feeling as if he had seen something truly remarkable.

After the tour, we stopped in the gift shop so that my son could claim his prize, a lollipop for finding all the designated items in the house. While browsing, he stopped to look at the refrigerator magnets. His eyes caught sight of Tom Sawyer whitewashing a fence and his fingers snatched the magnet. Turning to me he exclaimed, “I need this. This was in the book. The book we read. I have to have it because it will remind me of you, because you read me this book.”

How could I say no? We planned the trip to appease me, but his enthusiasm far exceeded mine. And I was happy to have had someone with whom I could share the experience.

Elizabeth Jaeger used to travel the world extensively until she decided to stay home and raise her son. Now she and her family take local trips to explore areas closer to home. She is currently earning an MFA degree in creative writing at Fairleigh Dickinson University where she is an assistant editor at The Literary Review.