|

an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins

|

ALFIE, ELEPHANT GRASS, AND A JAGUAR:

A Visit to the West of Ireland for the

Kenny-Naughton Festival

An Essay by Thomas E. Kennedy

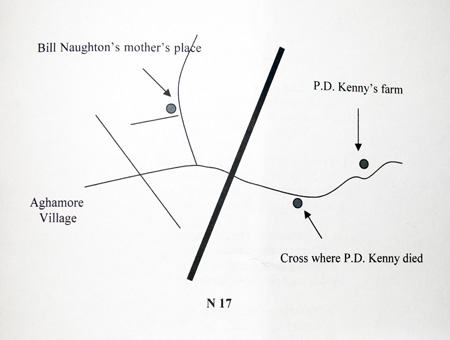

It seems I am to read at the so-called “Kenny/Naughton Autumn School,” 28-30 October 2011. My host is the chairman of the event, Paul W. D. Roger, who co-hosts it with the Mayo Arts Office and with Bill Naughton's widow, Ernas—who was born in Austria and resides in the Isle of Man where Bill died in 1992s—as patron. Paul Rogers’ e-mails are laconic but he, I am to learn, is anything but laconic; he is the polar opposite of laconic I will learn as he drives me in his brand new black Jaguar sedan around the vast farmlands of elephant grass surrounding Aghamore, on narrow dirt roads, to be shown, inter alia, the tiny cross on the side of one such road where the writer, P. D. Kenny (1862-1944), at the age of 82, fell, suddenly dead, from his bicycle. Kenny once described himself as “the most unpopular man in Ireland…”

Peter Jackson drives me from Dublin airport in a rented black Volkswagon to the Claremorris Hotel, just south of Knock, where I am to spend my first night. It is one of the modern buildings thrown up after a local priest successfully lobbied for funds to have the airport at Knock constructed at a cost of somewhere over 70 million Euros. The expense was justified by the fact that enough pilgrims want to flock to the area to see where Our Lady of Knock appeared on the evening of August 21st, 1879 to Mary McLoughlin, the housekeeper of the parish priest; Mary was astonished that evening to see the outside south wall of the church bathed in a mysterious light: There, in short, were apparitions of the Blessed Virgin, St. Joseph, and St. John. In 1971, the Church approved that the apparition was “quite possible”—sufficient recognition to merit an airport at Knock which has increased tourism to the area manyfold.

We have difficulty finding the restaurant where the evening dinner is to be held, and the rented black 4-door Volkswagon wanders back and forth on the rain-sleeked side roads for some time before we find the place, tucked away in a wood. Only one other person has shown up for the dinner, and the Chair, Paul Rogers, has to hurry off for he has to reprint the program. The reason for this is that the fellow who is one of the main speakers has returned, shaken, to London by train since he is terrified of flying and has been seriously unsettled by the flight into Knock.

“‘…she wanted me to go for a trip to the West of Ireland, and I said I wouldn’t,’ said Gabriel moodily. ‘O, do go, Gabriel,’ [his wife] cried. ‘I’d love to see Galway again.’ ‘You can go if you like,’ said Gabriel coldly.”

—James Joyce, “The Dead”

In “The Dead,” Gabriel Conroy is accused of being a “West Brit” because he is more interested in European culture than the original culture of Ireland, specifically of western Ireland. The train connection between Dublin and Galway is easy enough, but recently when I was invited to read at the Kenny-Naughton Literary Festival in a tiny village called Aghamore in what seemed to me a remote part of County Mayo, I learned that remote is a state of mind.

I am driven from Dublin airport to Aghamore by an Anglo-Irishman named Peter Jackson, a dark-haired talkative man of great patience who teaches high school in the western Danish town of Struer (pop. 10,000) at the base of Limfjord where the oysters are the best I have ever tasted. Peter also invites me to stay a night on his Uncle Jim Coleman’s farm in Roscommon, nearby. Then Jim Coleman’s 10-year-old granddaughter, Claire, googled me, told her teacher what she had learned from my website and, via Peter Jackson, asked me to bring some of my “stories for children” to share with her school class.

How could I ever say no to a free trip to Ireland or to a 10-year-old girl who lives in a tiny village and is interested enough in literature to google a little-known Irish-American writer who lives in Denmark, excited that I would be visiting, even though I have not written more than a couple of stories which would be suitable “for children”?

Colm O'Donnell, the author, and Peter Jackson at the Aghamore festival

But I am getting ahead of my story.

In the Claremorris Hotel, where Peter Jackson is to collect me early that evening for the opening of the literary festival, a ballroom dancing festival is also about to begin. The lobby is crowded with enthusiastic chesty men in blue blazers and neckties and women in delightfully dressy dresses. I've always been a sucker for a comely adult woman in a comely dress, and the woman who sits down beside me on the lobby sofa, wearing an elegant gray and white silk cocktail dress, sits in fact on my Burberry and is ignoring me in an irresistible manner. But I haven’t time to dally. I have to go out into the dark and into the rain. Gently I tug my coat from beneath her – happy that coat! as Bloom might have said – and she turns to me.

“Are you leavin’ me, then?” she asks.

“Alas I must but it’s breakin’ me heart,” says I which earns me a reward of the twinkling of her blue eyes and that quality of smile that women on occasion dole out to a man who passes her muster.

So the evening dinner is attended only by myself, Peter, and Mrs. Ginny Waln, a widowed American woman who is bravely and with dignity weathering her macular degeneration. She lived in Cape May, New Jersey until she and her husband retired here because they had spent happy vacations in Aghamore for many years. Now she is alone, and I offer my arm to lead her to the empty table in the back of the restaurant; a receptionist at the door asks us, “Do you have tickets? You’ll need tickets.” The woman on my arm says, in New Jersey-accented English, “Pay her no mind. She doesn’t know what she’s talking about.” Ginny, Peter and I dine on salmon and Indian chicken and merlot and then we’re off to the festival opening.

once a year for the Kenny-Naughton Autumn School Literary Festival

By nine p.m. we find the venue, a pub that was founded by one William Waldron in 1862 and inherited by the Rogers’ family—Paul’s father—in 1956, allowed to function until 1961, when the bartender moved to America, whereupon Paul's father, because he was a teetotaler, he shut it down. It opens only once a year for the Kenny/Naughton Autumn School literary festival. The pub has clearly been closed for fifty years. (No one seems to have noticed that this is the 50th anniversary of its closure.) The bottles on the shelves behind the bar are jacketed in dust. Only a handful of people are present yet, but Paul’s brother, T. J. Rogers, young and tall and smilingly taciturn, has set up a Guiness tap behind the bar and draws a glass for me. He explains that the previous publican was not only Aghamore’s bar owner but also its mortician. When the Rogers brothers unsealed the pub to ready it for the festival nineteen years ago, two coffins were in evidence on the bar, presumably empty. The other area of the bar is for the living and the thirsty.

T. J. pulls out from beneath the bar a stack of shrouds, some still folded and in their original cellophane wrapping, with an inspection number on them. They are sewn from an odd, shiny material of a brown color with tassels roughly over the nipples and legends inscribed down the breast, some in French, some in Latin, some in English:

A visitor's map of County Mayo: Here is Cong, location of the Homeric fist fight between Victor McLaglen and John Wayne in the film The Quiet Man; Westport, location of Matt Molloy's; Achill Island, location of the Heinrich Böll Cottage; Knock, where it is "quite probable" the Blessed Virgin appeared in 1879; Aghamore, location of the annual Kenny-Naughton festival. To the south is Galway and the Aran Islands where Miss Ivors tries in vain to interest Gabriel Conroy in visiting in Joyce's "The Dead."

In the morning, with great effort, I resist a full Irish breakfast, then am off, feeling virtuous, with Peter and his 84-year-old Uncle Jim to explore the green rolling expanses of grass in the valley of the Partry Mountains.

We stop for a lunch of vegetable soup in the Percy French Hotel in Stokestown, Co. Roscommon. French (1854-1920) wrote many songs that my father used to sing in New York—“Abdul Abulbul Amir,” “The Mountains of Mourne,” “Eileen Oge (The Pride of Petravail),” about how the hardest-featured man in Petravail stole away the prettiest girl in town by ignorning her.

The program for the second night of the festival includes a reading by myself from my newest novel (Falling Sideways, Bloomsbury, 2011), a reading of poetry by Iggy McGovern, a professor of physics at Trinity College in Dublin who has published two collections of poems, and a story by Tom Heneghan who, the program tells, was born in Belcarra “in the year of the big snow.” There is also a storyteller, Vincent Pearse, who tells one about a woman who roasts a drake and, because her guests do not show up, eats the whole bird by herself, then goes to the priest to confess the sin of gluttony, but she cannot remember the word so she attempts instead to describe the irresistibility of her temptation: “Ah there he was, Father, lyin’ there on the table with his beautiful brown skin and his lovely brown legs spread open. I couldn’t help but devour him, Father. Then I was hungry for him again in the morning and had a bit more of him then, too, Father. What was left of him, I fed to the dogs.” Vincent Pearse's talents are clearly Homeric for he is still by the fire place, still surrounded by a group of enraptured people when Peter and I slip away at half past midnight.

,%20chairman%20of%20the%20Naughton%20Society,%20holding%20a%20copy%20of%20Thomas%20E.%20Kennedy%27s%20Greene%27s%20Summer,%20published%20in%20Galway.jpg)

Paul W. D. Rogers (left), chairman of the Naughton Society, holding a copy of

Thomas E. Kennedy's Greene's Summer, published in Galway

Sacred Heart of Jesus, I place my trust in Thee.

Je suis L’immaculée concepcion

Conceptio Immaculata Sum

Those still wrapped are labeled “The Dublin Shroud & Frilling Co., Ltd., 32 Parnell Square, Dublin 1” and have style numbers on them—Habit 901, Habit 566, Habit 364.

“I suppose the customers could not complain about the fit or style,” someone comments.

T. J. says, “These are at least seventy years old,” and produces a cap of the same shiny material and odd brown color that would have been placed on the head of the corpse – it looks rather like a brown dunce’s cap. I wonder if the color is meant to symbolize the earth.

The fireplaces are loaded not with peat, but wood, and they crackle, giving heat and light in each of the four rooms of the pub, fighting the chill that emanates off the solid white stone walls. Paul – a bright, smooth-faced man in his mid-forties with black hair, whose shirt is sufficiently unbuttoned to reveal the grey-black curls on his chest – moves about the rooms of the pub, speaking rapid, word-filled greetings to each person by turn. Finally, around ten p.m., he tells me it is almost time to start, and T.J. kindly taps me another Guinness. I am reminded of social events at conferences in Spain and Portugal where drinks and tapas were served until eleven p.m. whereafter the guests were invited to the dinner table. I trust this event will not follow that model.

By now, there are perhaps twenty-five people present with one or two stepping in out of the rain every few minutes. I take a seat next to the stone wall which radiates a flesh-penetrating chill. I gaze longingly at the crackling fireplace across and down-room from me.

The Program for the Kenny-Naughton literary festival

At the wobbly blond lectern, Paul Rogers leads off with a few words about Bill Naughton and P.D. Kenny. Bill Naughton (1910-1992) is best known as the author of Alfie—both novel and screenplay, which was Michael Caine’s breakthrough film in 1966. The screenplay won Naughton an academy award nomination that year. He was born in Ballyhaunis, Mayo. Though the Naughton family moved to England in 1914, Aghamore remembers Bill. A plaque commemorating his visit to Aghamore in 1945 is on view at the village square. (I am later to learn that Bill's granddaughter, Anita, who waitressed for ten years at Tea & Sympathy in Greenwich Village in New York, published a book in 2002 about the restaurant.)

Paul’s words turn to P. D. Kenny (1862-1944), born in Aghamore, later moving to England where he would become a friend of Winston Churchill, then returning, a writer of social critique with a crisp, clipped British accent that could only have annoyed the local Republicans. Kenny was requested by Yeats and Lady Gregory to chair a debate about Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World—which startled him sufficiently to express his surprise because he had thought himself “surely the most unpopular man in all Ireland.” Kenny ended his days impecunious enough that he wound up sleeping in his own barn after losing the house he had inherited from his parents. However, a fine headstone has been erected on his grave.

It is these two writers we are gathered in this shut-down pub to celebrate. The celebrants that first night are myself, Hazzel McLynn-Lloyd, and Colm O’Donnell. I am grateful that my reading – from my novel In the Company of Angels (Bloomsbury, 2010)—is first; I would not like to have followed either, most especially not O’Donnell.

Colm O’Donnell is a farmer, forester, shepherd and sheep dog trainer from South Sligo, about whom it has been written that his “voice is as sweet and soulful as the tune of his flute.” This evening he gives a performance which consists of equal parts song, philosophy, rhythmic step with the heel of his boot on the bare wood floor, the song of his voice and the song of his flute. He concludes his presentation by singing acappella a waltz while spinning Hazel who, when he picked her out to dance with him, whispered anxiously to me, “This was not planned!” Yet she dances beautifully, gracefully plump with an appealing pretty face, just as she gracefully read selections from Naughton’s work. Naughton needs, however, no memorial for anyone who is old enough to remember Alfie as Michael Caine (and Dionne Warwick) and not Jude Law.

After the sessions, T. J. is there drafting glasses of stout, and where the coffins might have been, sandwiches and cakes are spread out on the bar. But soon the widow Waln is ready to be taken home, and Peter and I, having traveled since early morning, seize the opportunity to take an early night. I halfway hope that the ballroom dance festival is still in swing at the Claremorris Hotel so that I might see the sparkling-eyed lady who sat on my Burbury, but by the time I get back only the men remain, smoking and swayingly hoisting pints beneath the dripping overhang outside the glass doors, tie knots broken, jackets hanging open.

The countryside of West Ireland (photo by Walter Cummins)

Boys, oh, boys, with fate it’s hard to grapple

French was born near Elphin in Roscommon and is commemorated by at least two bronze figures of himself on public benches—in the main square of Ballyjamesduff (one of his songs is “Come Back Paddy Reilly to Ballyjamesduff”—which means “The Town of Black James” in Anglicized Irish) as well as a bench on the Grand Canal in south Dublin, just across from the bench on which sits a likeness of Patrick Kavanagh (1905-67), author of the masterful “The Great Hunger” (which is not about the potato famine).

Of me eye, boys, Eileen was the apple

And now to see her walkin’ to the chapel

With the hardest-featured man in Petravail

Boys oh boys, hear me when I say

When you do your courtin’ make no mistake

If ye want them to run after you

Then look the other way

Cause they’re mostly like the Pride of Petravail.

We decide to visit Achill Island to see the Heinrich Böll Cottage—a writers colony. On the way we stop in Westport, a town of perhaps twenty thousand, where we take a pint at Matt Molloy’s on the high street. Jimmy the bartender, it turns out, is a son of Matt Molloy, the flutist of the Chieftains who played the haunting theme song, “Women of Ireland,” from Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 film version of Thackeray’s 1844 novel Barry Lyndon. I ask Jimmy if he is a musician, and he tells me he is more interested in surfing, will be visiting Australia soon to do so.

However, the light on this overcast late October day, as we roll across the causeway onto the island, is less than inspiring. The fields and hills stretch and roll desolately, gray-white sheep grazing here and there in the charcoal gray grass.

A road in West Ireland (photo by Walter Cummins)

Back in the car, up and down hills, weaving through corkscrew squiggles of the narrow roads, the black VW rolls north along the N59 toward Achill—the largest Irish island. Henrich Böll, born in Cologne in 1917, had visited Achill regularly during the 1950s and ‘60s; his experiences of western Ireland are described in his book Irish Journal. Böll won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1972 and died in 1985.

Our literature about Achill describes that the quality of the light has attracted many artists to spend time there—Alexander Williams, Robert Henri, and Marie Howet.

We stop at the Achill Sound Hotel to ask directions to the Böll Cottage, and the man we ask—perhaps starved for an audience—couches the directions he gives in a nonstop monologue which flows so quickly I cannot follow its connections and am soon lost among his well-intentioned words. I notice once again that the Irish are forever telling jokes but seldom laughing.

Following what we think are his directions, we are soon on what seems to be the wrong road. Uncle Jim, from the back seat, looks out over the flowing, sloping gray meadows and says, “You wouldn’t want to spend the winter here.”

Peter hails down a large van at a crossing. The woman driving says she will lead us to the cottage and takes off speeding through the curving hills so that we keep losing sight of her. Finally, however, she stops and points to a low series of buildings which apparently is the Cottage. She does a broken-U and is gone as the two of us step out of the VW into the damp wind – Uncle Jim opts to remain in the warm, dry automobile.

A sign on the gate identifies Böll Cottage. In German and English, it requests respect for the privacy of the artists in residence. It is clear to me that were I to spend any length of time here, privacy would be the last thing I desired – but I am a city boy who feels hemmed in by open space, no longer at home in a town that has fewer than Copenhagen’s 1,525 serving houses.

In the morning, after a comfortable night’s sleep on Uncle Jim’s farm, we briefly meet young Claire, whose shyness my very best smile and banter fail to unlock—though I will discover after we have left in the VW that she has slipped a note in my bag: “Thank you very much Thomas. Claire.”

A note from young Claire

As we pull in outside Paul’s house again, to pick up Peter’s rented car, there is a collie racing around the Jaguar. I ask if that is Paul’s dog, and he says, “Ah, no. That dog is quite mad,” and I realize that the collie is trying to herd the Jag to the point that I fear it will be crushed beneath the wheels, but the dog is too quick and intent on getting the car to do as it ought.

Time is short to make our flight from Dublin, and we still have to cross a wide stretch of the country, but I have already decided that there is no sense in worrying: I have surrendered myself to the meandering roads and hairpin turns of Irish time. And sure enough Peter’s rented VW is delivered back to the airport in Dublin with nearly a half hour to spare before our flight.

As we are herded through security, removing belts, shoes, jackets, emptying pockets, I notice a familiar tune playing on the Muzak which it takes me a moment to place: It is the theme from Alfie. It occurs to me that I will never have the same relation to that song, will never hear it without thinking of the elephant grass, the dusty pub, the music, the shrouds, the stories, the stout, the people – Paul, T.J., Peter, Uncle Jim, Claire, Ginny, Colm O’Donnell, Hazel, Breda, all of them – and of those days of cordiality in Aghamore.